The Sahara desert as we know it today is an arid and inhospitable territory, not suited for human or animal life.

For how harsh it is, it’s hard to imagine it was ever much different, but in recent times it has been discovered that the Sahara wasn’t a desert at all in the past, but rather a lush green area, full of bodies of water and animals nowadays associated with many countries of Central Africa.

Scientists have discovered that Earth shifts its axis quite regularly, around every 20.000 years, a phenomenon that causes changes in climate, and consequently in everything that depends on that, such as flora and fauna. The Sahara is one of the areas most affected by this change, with a gradual process that affects its biomes deeply.

During the early and mid-Holocene, the Sahara went through different periods, alternating humid phases to arid ones, each lasting about 2000 years, while still being lush. From 3000 B.C. to 1000 B.C., the western Sahara went through what’s referred to as the Nouakchottian phase, a humid one, when the climatic pattern of two contrasting seasons, a more or less longer dry season and a generally shorter rainy season, became characteristic in the territory.

However, after 5000 B.C. the Sahara territory was becoming gradually arider and arider, despite the alternating phases, forcing the people who were living in the northern areas to move south and look for more humid latitudes to inhabitate.

Table of Contents

Dhar Tichitt

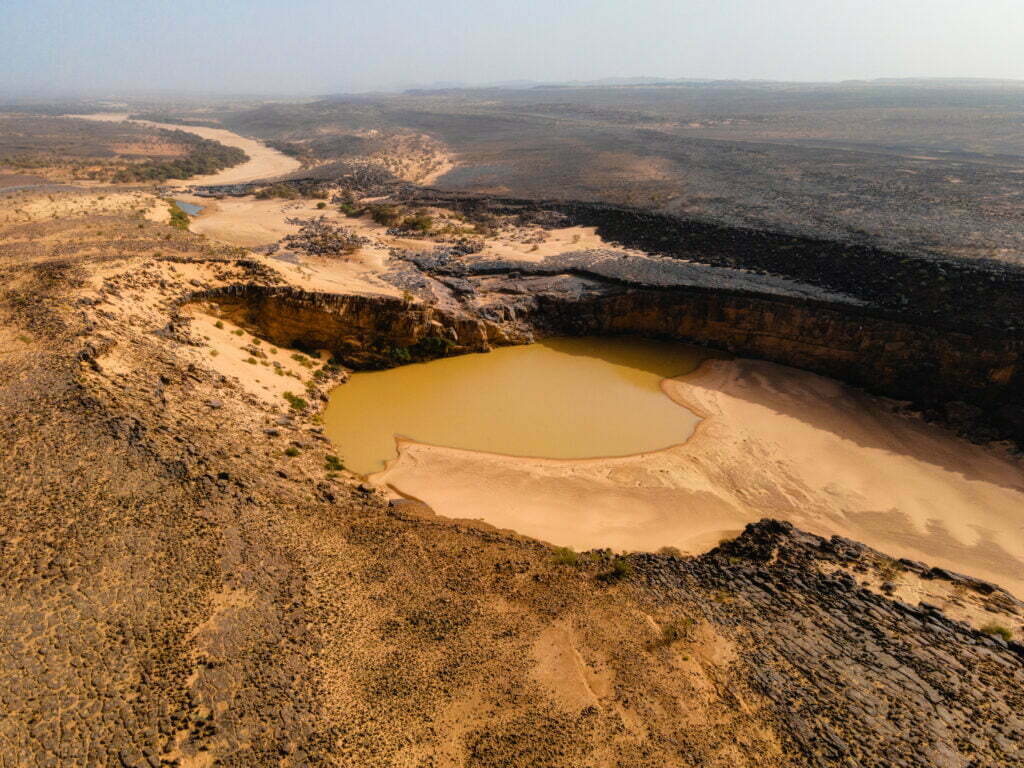

That’s how populations found the Dhar Tichitt region, in the South-Central Tagant region of Mauritania, an area with a series of lines of steep sandstone cliffs, standing on average 60m above mainly sandy flats and interdunal depressions.

If we consider the area from Dhar Tichitt to Dhar Oualata, an almost 400km long series of the cited sandstone cliffs, it has been discovered that more than 500 villages were constructed and inhabited during the Neolithic. Nowadays, the most notable of those is Aghrijit, a protected site since 1991, about 30km away from the town of Tichitt.

Before we talk about Akreijit, we need an overview of the situation in Dhar Tichitt during the Neolithic.

Dhar Tichitt in the Neolithic

While the Sahara kept going in its transition of becoming the desert we know today, there were some areas that resisted the climatic change better than others, mostly due to the conformation of the territory. As in all other places on Earth and beyond, the first and most important thing needed for human life is water, and those areas were the ones that were able to maintain a good balance between the contrasting rainy and dry seasons.

Thanks to the archaeological evidence, nowadays we know that the sandy flats between the sandstone cliffs were once the recipient of the bodies of water running through Dhar Tichitt. There were also many lakes and streams found on the plateau and the flats, full of water only during the rainy season.

However, one of the most important factors to the success of life in the Dhar Tichitt was the discovery of bulrush millet, growing in its wild variety in the area, and of wild grains, though used less than the millet.

Life in Dhar Tichitt

The sandstone cliffs of the Dhar Tichitt in South-Central Mauritania were inhabited by Neolithic agropastoral communities for more than one and half millennia during the Late Holocene, from ca. 2300 to. 500 B.C.

There is no real evidence of prior settlements, which points to the influx of people moving from the drying northern Sahara to the more humid south.

As previously stated, this period of the Holocene was characterized by two contrasting seasons, one dry and the other rainy. This drastic difference naturally forced the population to adjust depending on the availability of water, their main need.

The numerous settlements that animated the 44km long Dhar were all constructed on the edges of the cliffs, closely following the hydrographic network. The villages consisted of heavy dry-stone masonry structures suited for life and storage of resources.

The idea is that during the rainy season the people would live in the villages on the plateau, as the valleys of sand were mostly full of water.

A few small surface sites have been found below the cliffs, in the sandy interdunal depressions. These sites are probably grossly underrepresented due to the difficulty of finding them where there is drifting sand.

During the dry season, the water was only available in the deepest points of the valleys below the cliffs, sometimes quite far away from the main villages. That’s why they created these small temporary settlements that were eventually going to be erased by the rainy season. Faced with a predictable dry season water shortage, the Dhars Neolithic people devised a robust strategy to enhance their livelihood; a short-range, pulsatory nomadism.

The practice of semi-nomadism is one of the most tangible reports of life in the Neolithic that we can observe today, as about 10% of the population of Mauritania (ca. 400.000 people) still follow this living style.

Water sources were most of the time within walking distance range. Groups could have walked up to 5–10 km to fetch water in large clay vessels or goat skins, to be kept in large storage jars in the household compound. Groups of herders probably took livestock herds to camping areas for most of the duration of the dry season. They left their traces in the archaeological record in the form of shallow scatters of food waste, broken sherds, and grain processing stone tools.

The food procurement system during the occupation of the Dhar Tichitt was agropastoral. It may have consisted of millet cultivation and livestock herding in the vicinity of the main settlements during the wet season, and, in the dry season, besides herding, also fishing and gathering of wild grains and fruits from temporary camps located near water sources. Hunting seems to have been practiced throughout the year.

As noticed in the botanical evidence, the dichotomy present in the way of settling was also seen in the agriculture, as the villages on top of the sandstone cliffs of the Dhar were dominated by millet growing, which could be considered their staple food, while in the dry season settlements the preferred option was the gathering of wild grain varieties, which provided supplementary and emergency food.

To this day, bulrush millet still grows wild in some areas of Dhar Tichitt.

The abandonment of Dhar Tichitt

Around the year 500 B.C., a dry spell hit the area, which started to change the climatic pattern the people of Dhar Tichitt had known for almost two millennia. The alternating dry and rainy seasons stopped, and though the Tagant region had been the most resistant one, it was only a matter of time until it completed the desertification.

The abandonment of the whole area was probably gradual with small groups of families moving south and southeast in search of better environments. These populations may have later contributed to the rise of the Ghana Empire, which dominated West Africa until the 13th century A.D.

Visiting Akreijit in 2022 – Getting to Dhar Tichitt

With now more than 4000 years of history, Akreijit and its ruins stand as one of the most ancient and interesting sites in Mauritania.

We visited the Neolithic village and its modern-day counterpart on a day trip from Tichitt, the main settlement of the Dhar, which is still inhabited and well maintained.

Reaching Tichitt from Tidjikja is a tedious and quite long journey, but it can be done in a day of driving. I suggest using this road to avoid the heavy inconvenience of having to cut through 200km of Aoukar and its tall sand hills speckled with bushes that can easily stop any vehicle. The latter is what we did, but that’s a story for another day.

Luckily, from Tichitt onward the road is as simple as it gets, coasting the cliffs of Dhar Tichitt for 30km until the new village of Akreijit is reached.

Still built next to the cliffs that hosted the numerous settlements of Dhar Tichitt, the recent village doesn’t follow any trend of the area in terms of city engineering. The houses are all distant from each other, there is no trace of a main square or of a market and, probably the biggest difference, it’s been built below the cliff. There is little to no risk for the village to be flooded since the process of desertification completed, so they decided to make it more accessible for people to travel toward Tichitt and get back.

While our interest was the ancient village, we still decided to visit the new one and make friends with the local children, which all came with us everywhere we went once we stepped foot out of the car. Some of them were so kind as to let us get a photo of them.

Like it’s often the case, villages look better from above, which is why we climbed the cliff above Akreijit. With our band of Mauritanian kids, we went up to one of the many plateaus that once hosted our predecessors. The view from above permits you to get in sight every house, the village’s palm grove, and the other complexes of cliffs.

Ancient Akreijit is a couple of kilometers north of the new village, where the guardian can always be found by asking around.

Getting to the site is simple, and it also holds a few highlights; the rock formations of the cliffs are beautiful in this area (which is near the famous Elephant Rock of Makhrougat), and about halfway through the road it’s possible to find a lot of smooth and circular rocks on one side of a cliff, which is quite unusual. We suspected they came from what was possibly a lake.

Upon reaching the base of the cliff hosting the site, there’s a little building that serves as a visitor’s checkpoint, where you can read about Akreijit and see some of the artifacts preserved by the guardian.

From there, a long stairway leads up to the ruins of Aghrijit.

The structure of Akreijit

The dimensions, shape, and internal structure of the large Neolithic villages of Dhar Tichitt, Walata, and Nema vary considerably; Akreijit is fan-shaped. They nevertheless have essential common characteristics, namely an architecture based on dry stones, a honeycomb arrangement of domestic units, networks of alleys, and public squares.

Located on the edge of the cliff escarpment in Dhar Tichitt, Akreijit has 177 enclosures spread over an area of 15 ha, a series of alleys running north-south and east-west that lead to open spaces in the center-west and northwest.

The enclosures are organized into 11 clusters of adjacent domestic units. The number of units per cluster varies from 3 (two cases) to 37 (one case), and the area of the enclosures from 75 to 2,394 m^2 . The detailed study of the constructions revealed important architectural modifications: the change of the course of a wall, the opening of a new lane, the enlargement or reduction of a square or a public place.

The relationship between private spaces and public spaces seems to have constantly changed. The regional center of Dakhlet el Atrouss and the large village of Akreijit present interesting situations.

In Dakhlet el Atrouss, despite its 550 enclosures, 50.28 ha (62.45%) were devoted to public space against 30.22 ha (37.54%) in private space. In Akreijit, on the other hand, 11.25 ha (75%) was private space for 3.75 ha (25%) of public area.

A typical home in Akreijit

The excavation of one of Akreijit’s enclosures revealed the internal organization of a medium-sized domestic unit. Enclosure 50E is in the northern portion of the village and dates from 550-450 BCE. Oriented east-west, it measures 450 m^2 and has an overall diamond shape. A close examination of the construction reveals interesting facets of its history. The perimeter wall (1.5 m thick by 1.5 to 2 m high) has an entrance door to the south and two walled doors to the north and west. The northern gate may have been following the construction of a new enclosure on the northern flank, in a space previously empty of structures, unless relations between neighbors had deteriorated, leading to its closure to prevent comings and goings between the two domestic units. As for the west door, it was closed after the development of a public square on the western side of the enclosure.

The interior space is distributed among five living units arranged around a central hearth. They are more or less rectangular, with areas ranging from 8.4 to 12.4 m^2. Two of the best preserved structures (fig. 3) have E-shaped plans. The other three have been completely eroded, with the stone blocks lying directly on the sandstone substrate. A small internal enclosure built at the eastern corner must have served as a shelter for the small livestock and as a storage area for foodstuffs on platforms on stilts. All things considered and taking into account the state of preservation of the data, the number of grinders, millstones, anvils or work tables and hammerstones inside the habitats is significant. It is therefore likely that enclosure 50E was inhabited by an extended multi-generational family.

The extended family seems to have been the optimal form of the basic unit of the Neolithic agro-pastoral societies of the Dhar Tichitt, Walata, and Nema.

The perfect depiction of the Tagant

The guardian showed us some tombs, gave us a history lesson and brought us around through the ruins and towards the border of the cliff, where he told us we were going to find some cave paintings.

The view from Akreijit is immaculate. Mauritania is all there; the history of the people, the ancient settlement, the imponent Dhars, the boundless desert speckled with trees and salt deposits, and the memory of the changes the Sahara went through.

It’s always special imagining a place for what it was in the past, but in Akreijit it has to be one of the most difficult things to do. This area changed drastically in the past thousands of years, and imagining it for the lush green territory it once was, full of water, animals, and people requires an extremely creative mind.

Our visit to ancient Akreijit was brief but magical. It taught us a lot of information about the ways of living in Neolithic Mauritania, something that is not heard of every day.

Itís nearly impossible to find well-informed people for this topic, but you seem like you know what youíre talking about! Thanks

Thank you so much! Yeah, it’s not a topic with much info online. This was only possibly due to my extensive time spent in Mauritania, and an impossible amount of research to be honest. I felt like I had the pleasure of narrating a lost history. I’m really glad you appreciated it.